Future Rage: Bubbles, Fuckwads, And The Illusion Of Control

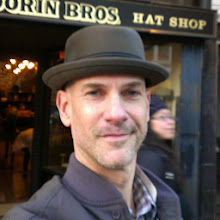

Here's professional bubble-smith Sterling Johnson on Stinson Beach last month, blowing giant bubbles as children chase after them.

If you were to ask me to name one thing that progressives and Tea Partiers, Israelis and Palestinians, Indians and Pakistanis would all agree is a nice, positive, peaceful image, something no one in or near their right mind could argue about, I'd probably say blowing giant rainbow-colored bubbles on the beach as children chase after them.

Or would have said that before today.

Because if you look at the YouTube page where this video is posted, you will see that the comments on this peaceful, lovely, utterly uncontroversial vignette have degraded into a bitter flame war.

@WTFYouPoser ur profile says u r 24, so u really? must be just an idiot. @magus424 and @sterlingjo told u the same thing that he was being sarcastic

@WTFYouPoser the reason y u must b really young, or just an idiot from planet retard, is cuz u r not old enough or wise enough to realize that he was being sarcastic!! This is not the first time someone has done this, I have seen this before! i'm pretty sure if u are? able 2 comment on youtube, that means u r at least passed the elementary school phase, almost everybody in this country that went 2 school did some type of experiment with bubbles where u make bubbles with tied string or the other

@WTFYouPoser lmoa! how old r u? if u r under 14 then just disregard this. I am just guessing u r young by the way u spelled stupid, its not 'stoopid' sweetie. I can understand if you were trying to shorten a word or phrase but u were not, u actually added an extra letter. I had to address this? issue, cuz if ur gonna come at me please make sure for your prides sake, that u r not an idiot from planet retard!!

The video, as I say, has been up for a month. One can only imagine how far it will descend into the depths of ad hominem hostility over the next 10 years.

This might just be an object lesson in what's known as John Gabriel's Greater Internet Fuckwad Theory.

An oft-quoted research paper from John Suler in the journal CyberPsychology and Behavior explains that the insular and usually solitary experience of being online bypasses the brain's "social circuitry" and brings out the worst in us:

Suler, a psychologist at Rider University in Lawrenceville, N.J., suggested that several psychological factors lead to online disinhibition: the anonymity of a Web pseudonym; invisibility to others; the time lag between sending an e-mail message and getting feedback; the exaggerated sense of self from being alone; and the lack of any online authority figure.

Dr. Suler notes that disinhibition can be either benign — when a shy person feels free to open up online — or toxic, as in flaming. The emerging field of social neuroscience, the study of what goes on in the brains and bodies of two interacting people, offers clues into the neural mechanics behind flaming. This work points to a design flaw inherent in the interface between the brain’s social circuitry and the online world. In face-to-face interaction, the brain reads a continual cascade of emotional signs and social cues, instantaneously using them to guide our next move so that the encounter goes well. Much of this social guidance occurs in circuitry centered on the orbitofrontal cortex, a center for empathy. This cortex uses that social scan to help make sure that what we do next will keep the interaction on track.

Research by Jennifer Beer, a psychologist at the University of California, Davis, finds that this face-to-face guidance system inhibits impulses for actions that would upset the other person or otherwise throw the interaction off. Neurological patients with a damaged orbitofrontal cortex lose the ability to modulate the amygdala, a source of unruly impulses; like small children, they commit mortifying social gaffes like kissing a complete stranger, blithely unaware that they are doing anything untoward.

The Journal of the Association for Psychological Science tells us that road rage is more or less the same thing — an artificial sense of isolation which also isolates us from our frontal cortex:

It turns out that all of these actions can be fostered by the feeling of security generated by the locked doors of your car. Psychologists assert that drivers may develop a sense of anonymity and detachment in the confines of their vehicles. And tinted car windows may be more than a safety hazard. They may even further detach drivers from the situation during an aggressive incident (Whitlock, 1971; Ellison-Potter, Bell Deffenbacher, 2001).

All of which may be true. Yet there are plenty of instances where this hostility expresses itself in public, without the benefit of locked doors or a computer session's isolation. Thanks to flight attendant Steven Slater and his exit, stage left, down the airplane's emergency escape slide, we've all heard of "air rage."

And now comes desk rage, too.

In my opinion all these flames and rages are manifold expressions of a single underlying psychological reaction to our modern age. Call it future rage.

My theory is that the contemporary lifestyle's many creature comforts, conveniences and technological enhancements comprise an environment so alien that it's beginning to bypass brain circuitry designed for a far more tactile and visceral world. The sense of control that we have over our world — push-button, air-conditioned, connected and mobile — may be illusory. I believe people feel, if less than entirely consciously, that they don't have control over much of anything.

That brings with it disconnectedness, and dislocation. Trapped in cars, in the flying tubes that are planes, in the particle-board boxes of office cubicles, even in the wireless harnesses of our mobile device-enhanced lifestyle, we are profoundly cut off from our tribe, our earth, ourselves. We lose the moderating, centering, grounding influence brought by those primal contexts. And the more we cut off we feel, the more we tweet, update statuses, comment, flame, honk, flip the bird, jump down the emergency slide, act out.

The pace of today's life just makes some people frustrated, people say, some a little too frustrated.

Perhaps. But I really think on some level it's a form of panic at a world that's gotten away from us.

Afterthought — Some readers may be too young to remember The Prisoner, the surreal and sublimely paranoid 1967 television series from the BBC. A secret agent (Patrick McGoohan) is kidnapped after he tries to retire from the MI5 and is taken to a deceptively placid island resort called "The Village". Comfortable settings and constant amusements thinly mask the individual's complete lack of control or identity. (McGoohan's character, now called Number 6, screams "I am a man, not a number!")

There are no fences, walls or guards around The Village. Those who attempt to escape and get back to where they came from (or who otherwise assert their individuality) are hunted down, surrounded and suffocated by Rover — a giant bubble. (Played with great conviction by a weather balloon.) At time time, a lot of people probably shrugged off the bubble-as-Gestapo metaphor as just another drug-addled image from the producers.

But in thinking about how a beautiful, fragile, giant bubble on a beach could be a vessel for rage and, ultimately, dislocation, I remembered Rover, and how that unpoppable, implacable bubble scared the crap out of me.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home